Jazz guitarist Harry Peacock . . . still plucking away at the strings and running his fingers down those frets at 80.

27 July 2018

It is jazz guitarist Harry Peacock’s birthday today. He is a young 80 years old and is one of the most respected guitarists to have entertained people in Cape Town.

Harry has been playing since his early teens, which gives him a career that spans 60-plus years. That’s a helluva journey and one that has its genesis in the most unlikely of sources – the coons!

For a man who says has been inspired by the playing of jazz guitar greats like Barney Kessel, Wes Montgomery and Herb Ellis, he is honest enough to say he owes his love of music to the coons.

“My interest in music began at the age of eight or nine when I first heard the coons,” Harry says candidly. “I was fascinated by the coons, by the ghoema, if you will.”

The colourful klopse strumming their “pan” and pounding their rhythms on the “kadoematjies” would have been a source of a great excitement for a young Harry as they danced down the cobbled stones of Bree Street where he lived.

“The rhythms fascinated me. I was absolutely taken with the music. There and then, my musical journey started. I had that rhythm in me.

At St Theresa’s Primary School in Wesley Street, one of Harry’s friends had a harmonica and he had a go at it.

“I discovered I could actually play a tune on it, in fact, I played a couple of tunes. My mother was quite impressed that at this young age I could play a tune.”

Harry’s love for music was further piqued by the sound of the pennywhistle played by another school friend. No problem for Harry: he swapped his harmonica for his friend’s pennywhistle.

This, at the age of 12, led to the next seminal moment in his music career.

Harry explains: “There was this fisherman guy, George, who used to board with my family. He had a guitar that he played in his room and I used to listen to him. I had my pennywhistle playing the kwela stuff and he strummed it on the guitar.

“He would go away to sea for a week or two. When he saw I was interested, he left his guitar at home for me to play while he was away. He was already showing me a couple of chords. That’s how I got started on the guitar, with a couple of chords and I took it from there. I realised I had a feel for it, and I was playing the ghoema coon music.”

As the pennywhistle supplanted the harmonica, so did the guitar supplant the pennywhistle.

“My brother, Herbie, who was a drummer, came home one day with a record featuring the Oscar Peterson Trio playing Tenderly recorded at Carnegie Hall in 1950. On guitar was Barney Kessel, and Ray Brown was on bass.

“I was already into jazz because Kessel was my main influence. When I heard him play with Oscar Petersen, I was hooked, really hooked.

“I started studying Kessel’s style. I also listened to Herb Ellis and Wes Montgomery. I was into different styles, catching a little bit off everybody. Later I started listening to younger guys like Diana Krall’s guitarist, Anthony Wilson.”

“Harry’s love for music was enhanced when he attended St Columba’s in Athlone where he featured in a number of concerts. Pianists Arthur Gillies and Vincent Kolbe also attended St Columba’s.

He finished his Junior Certificate and started his day-job career as an upholsterer. Music, however, was always there. His mother bought him his first guitar and he acquired his first electric guitar at the age of 16.

“I was already playing publicly with Herbie, Lennie Daniels was on piano and we had two others. The set of drums was called Beverley, so he named the group the Beverley Quintet.

“We practised at home and picked up a once-a-week gig at a dance studio at the bottom of Loop St. We were very amateurish, still getting into the swing of it. Jazz is a very intricate type of music.”

The group was into the sound of George Shearing, the blind British pianist who had a monster hit with Lullaby of Birdland.

“There was a piano player called Dougie Erasmus who headed a group called the Copacabana Band. When he heard me playing Shearing, he wanted me in his band. Shearing’s sound was the type of music they wanted in nightclubs because it was very mellow type of sound. Not a noisy type of sound. It was cool.

“The Beverley Quintet did not want me to go but they eventually agreed. That was in 1955, the year that the great saxophonist Charlie Parker passed away.

“The Beverley Quintet broke up after I left and I stayed with Dougie for a long time, more than 10 years we played together. We played mainly white clubs and what they call today corporate gigs, and at peoples’ houses for rich people.”

His stint with Copacabana was grueling at times. They had a contract at The Balalaika in Bree Street where they played nine months straight, six days a week.

“I used to get home around 3 in the morning and be up at 7 for my day job. I never give up my day job. Those days you couldn’t really make money out of a music career. I have never given up my day job, I carried on up till now.

“How I managed to live this long is, I don’t know. Actually it’s a miracle, you know what goes on in those clubs.”

For his 18th birthday his mother bought him the much-vaunted Gibson guitar but it met a tragic end. He lost it somewhere when it fell off the top of the roof of the car on the way to a gig.

“I bought another second-hand Gibson and my good friend, Raymond Johnson, before he died, gave me one of his guitars, an ARIA.. I’m still playing it 25 years later.

“The Gibson is still my favourite guitar, it has such a beautiful sound. All the US jazz players used Gibson. The Fender only came afterwards.”

After a few contracts in other clubs, Harry decided to go on his own. He started the Harry Peacock Quintet with an up-and-coming Gary Hendrickse on piano, the late Ronnie Green on bass and brother Herbie on drums.

“We played all over the show and added another saxophone player from Kensington, Archie Fisher. Our group opened the Kensington Inn.”

Although they were essentially jazz musicians, Harry recognised that they had to cater for the occasion. “Sometimes we played at a dance for a soccer or baseball club. We’d play langarm, with a little bit of jazz in between but mostly langarm . . . quicksteps and waltzes and slow foxtrots. It was quite fun because you could incorporate your jazz improvisation in it.”

His long career meant he rubbed shoulders with some of the legends of Cape Town music. One of them was pianist Tony Schilder whom he met at a jazz concert organised by Vincent Kolbe at Holy Cross in Nile Street, District 6.

“Tony Schilder was there as was [saxophonist] Harold Japhtha. They were two outstanding musicians. I played with them regularly. Tony gave me gigs during the week while I still had my quartet.”

Harry’s capacity to play different styles doesn’t alter his view that he is a jazz guitarist.

“I am regarded by most people as a jazz musician but I did play langarm a little bit, and of course, I started with ghoema. I was not much into rock and I was not much into jazz-funk either. People say ‘do you know Harry Peacock?’ and the answer invariably is ‘the jazz guitarist’.”

He is unequivocal about the role ghoema played in forming the musician he is.

“I am a Capetonian. As I said, I started out with ghoema, I can’t now say I don’t really like because that is what inspired me to be a musician. I have a very high regard for that, so much so, if I had my way, I would have joined the coons – but my mother wouldn’t allow me to do that.

“I would have loved to have put on that coon gear and be with those musicians in the middle and jumping around and playing. It really got to me. Of course, your parents wouldn’t have allowed you, ‘an English-speaking coloured’ – you know what I’m talking about – you would be downgraded as a ‘skollie’.

“I have to be truthful about this. I’m not going to say ‘no, I’m a jazz guitarist, I’m not going to play coon music’. No, I’m being very humble about it and that’s what it is.”

His favourite South African guitarists were Johnny Fourie and Kenny Jephtha .

“Johnny was very influential as far as I’m concerned. He was based Johannesburg but I spoke to him regularly. We also mustn’t forget Kenny Jephtha. He was already playing when I started. I used to get a lot of tips from him; I stole with my eye when he played.”

He had a high regard for the Dyers brothers, Alvin and Errol, specially Errol. “You can say he was a jazz guitarist, but he wrote his own music, like Cape ghoema, if you like. He was on that sort of kick. I really admired him for that.

“And of course, of the younger guys, there is Wayne Bosch. I think he is one of the most under-rated jazz guitarists in the country.”

Apart from Kessel and Ellis and Montgomery, Harry found the sound of George Benson “in his be-bop days, was absolutely outstanding; we all know what Benson did, he went all jazz-funk and he made a name for himself.

“I love the sound of Anthony Wilson, of Diana Krall’s band, and Biréli Lagrène who was raised in the gypsy guitar tradition. Very few people have heard of him but he is an absolutely outstanding guitarist.

If he had to put a group together of his favourite local jazz musicians, whom would we have? “I’d have either Tony Schilder or Gary Hendrickse on piano; Gary Kriel or Basil Moses on bass; and Cecil Ricca on drums.

“My singers would be ‘the Frank Sinatra guy’, Dougie Schrikker and Zelda Benjamin. It was a joy to accompany Dougie.”

Harry still does occasional gigs, mostly with Gary Hendrickse. “I still practise regularly two hours a day. I have to keep the fingers loose. At my age, you have to – and I have the time to do it.”

He doesn’t have any recorded material to his name except one studio effort with Harold Japhtha in 2003 at SABC in Cape Town. It wasn’t released commercially and each musician got a copy of it for posterity.

As he enters life as an octogenarian, Harold reflects on a life well lived. He accepts that jazz-funk has taken over from the jazz that he likes to play but he is sanguine about the future of the genre.

“The jazz front is doing very well. There are lot of up-and-coming, very talented musicians. Sometimes I do go out to listen to them but not often enough. At this age you don’t want to go out driving at night.”

He has no regrets about never having had a formal music education. “I can’t read music; I read with my ear and it was never a problem. The guys were so talented we could just get together and just get going. I never ever felt the need to go out and study.”

The highlights of his long career that live with him is the jazz concert in the City Hall with Tony Schilder – “it was packed out” – and being part of the support band for crooner Danny Williams at the Lux in 1968.

“He was a very naughty bugger. He took a skyf and he drank a lot.

“Still, he made quite a name for himself in England. The story goes that when they made the soundtrack of Breakfast at Tiffany’s with Moon River, the theme song, they had to toss up between Nat King Cole and Danny to do it. When Nat heard Danny’s version, he said ‘give it to Danny’.

“Danny Williams’ manager told me that story. I can believe it because Danny did a terrific job.

“I have no regrets about the life I’ve led. I’d do it all over again. I am very thankful to God for giving me the grace to do this. Sitting here, talking to you at 80 about it all, I never thought I would be doing it at this age. You go through quite a lot when you’re a musician.”

Have a great 80th birthday Harry. You deserve it.

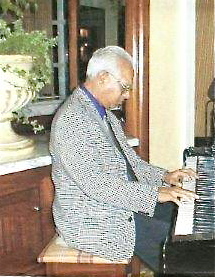

Harry Peacock with Gary Hendrickse on piano and Gary Kriel on bass jamming at a recent gig in Kensington.

Related articles

Gary Hendrickse: A class act who sould have given up his day job

Willie van Bloemestein: Mr Versatile and everybody’s favourite drummer

Ronnie Green . . . brought more than a touch of colour the the jazz scene

Errol Dyers . . . the quiet one but his guitar spoke volumes

Material on this blog is copyrighted. Permission has to be obtained to publish any part of it.