Saxophonist Harold Jefta who will be playing a number of gigs in Cape Town with his Swedish jazz group.

9 march 2016

Saxman Harold Jefta isn’t just an “elder”. He’s a lot more than that. Quite possibly, Harold is “the eldest”.

Eldest what? Eldest active musician who has his/her roots on the Cape Flats. Harold is a very fit 83 years old.

Most would have thought the “oldest” playing muso would be Abdullah Ibrahim (Dollar Brand). No, Harold’s older by a year. Both born in October, Harold in 1933 and Dollar in ’34.

One other thing that needs clearing up is Harold’s surname. He was born Jephtha but, living in Sweden for more than 50 years, he was forced to use the much simpler Jefta.

“It was so frustrating,” Harold says. “They just could not get their heads around the phth and I my name kept appearing as Jefta. Eventually I began using it, although my children use the original form.”

I’ll stick with Jefta for this interview.

Cape Town jazz lovers will be able to pay due respect to this elder next month. He’ll be appearing, along with his Swedish quartet, at a number of venues in a whirlwind visit to his place of birth. He’ll be at The Crypt, Kaleidoscope, Straight No Chaser, the Jazz Yard Academy and Winchester Mansions.

There is much to be said and written about Harold Jefta. This interview will be an abridged version of his long career. He is in the process of documenting his life in a book, unedited extracts of which are appearing on his Facebook page.

He was born in District 6 (like so many others of his era), before moving to Salt River at a very young age.

Those were happy days hanging around with his cousin Kenny Jephtha, himself a guitarist of note and who was to become one of Harold’s mentors.

Kenny was inadvertently responsible for Harold ending up in the Maitland Cottage Home for Cripple Children for about five years – and that in itself led to Harold taking an interest in music!

“Kenny built me one of those scooters we were so fond of in those days,” Harold recalls. “I loved it and raced up and down the streets around Cecil Rd.

“Unfortunately, I had a very bad accident with it – I smashed my knee – and I was a patient at Maitland Cottage Home for about five years.”

It was at Maitland Cottage Home that Harold found himself listening to music constantly, either on the radio that featured bebop or swing, or to other boys who had to occupy their time productively.

“I used to play tunes on my bamboo pipe when I was 10. We were listening jazz on radio during the War everyday. I would try to emulate what I heard on radio.

A young Harold Jefta lets rip during a jam session in Cape Town before leaving to live and study in Sweden.

“I taught myself by looking at other guitar players. There was a guy at the Maitland Cottage Home called Johnny Paterson who I think became the first coloured jazz musician in Cape Town.

“He could play the guitar but he could also play the harmonica. He was the best harmonica player in Cape Town ever. He won a competition. I’m talking about around World War II.”

By the time Harold was discharged from the Maitland Cottage Cripple Home, at the age of 14, his family had re-located to Matroosfontein and it was there that his music career started.

“I could strum the guitar quite well and I could blow a few tunes on the bamboo. My father made me play for the local Christmas Choir band and – believe it or not – the local gangsters used to make me play for them when I hung around the neighbourhood.

“Not only did the boom rookers make me play for them while they danced the ghoema, they also made me smoke their boom.

“Of course, when you were young and you lived in rough areas, you were forced to show the other guys you were one of them. Otherwise you couldn’t walk the street at night. They were tough guys, very tough.

“For me, it was a just a show, just a pretence. I’d take their zol, take one or two puffs, but I would not inhale. You just had to show that you are one of them.

“I have always taken care of my health over the years. Most of the other guys were always drinking and smoking. That’s what killed them.”

During his late teenage years in Matroosfontein, Harold started spreading his music wings. At the age of 14 he had already had his first jazz gig with Kenny Jephtha who “was already a master guitarist”. He played the Benny Goodman stuff on clarinet.

He also did gigs with langarm groups like Wally Ruiters’ Dance Band and actually played at the opening of the popular Reo Hotel in Halt Road.

Interestingly, he could easily have been a neighbour in Matroosfontein with two other music legends. Both Robbie Jansen and Tony Cedras lived in the area. Their paths were to cross much, much later. In 1959, aged 22, Harold decided he needed to have a formal education in music.

“I spoke to [noted Cape Town jazz musician] Morris Goldberg about it. It became apparent there was not much scope for a coloured to study music seriously at home. I would have to head overseas [if I wanted to further my music education].

“By then I had already started playing with all the well known jazz musicians and I also had my own band, the Harold Jefta Quartet. Johnny Gertze was on bass, Mervyn Jacobs on piano and Raymond Hendricks on drums.”

Harold says he started the first non-white jazz club, St John’s Club. His quartet played Lester Young stuff. Although he says he played the way he felt, everybody told him he sounded like tenor saxman Young.

“We played Benny Goodman, Stan Getz and Charlie ‘Bird’ Parker material too. Parker died in 1955 but I’m still studying his music and I tour Scandinavia playing it. They call us the Charlie Parker Memorial Quintet.

“I still prefer bebop. I specialise in it. Charlie Parker is King.”

Harold had a stint South Africa with the Golden City Dixies in its early years and once played in Johannesburg with that city’s jazz giant, Kippie Moeketsie.

“He was amazed when he heard me. He said, ‘you know Harold, I’d rather fight you than challenge you on the sax’.”

When Harold got to Sweden, he spent the first six years “on the benches”, as he puts it, studying music.

“I came to Sweden not just to play around in dance bands and amateur bands. I wanted to become something a little more than that,” Harold says.

“I thought I knew too little, so I studied classical musical and for more than 20 years, I was involved with symphonic. I played bassoon. It’s a tough instrument, a beautiful instrument.”

Like so many struggling music students, Harold played dance music – sax and clarinet – while he studied to earn some money.

“I used to get into trouble with my teachers. They used to say, ‘we hear you played jazz last night, stop that bad music’. But I needed the money.

“My classical training gave me my clean technique; I can play mighty fast on my instrument. I passed all my tests in classical music but I had to have one extra subject, psychology, which I failed, probably because I was playing bassoon, clarinet, percussion, and piano. I had no time for psychology. I can play about 10 instruments.”

Harold’s passion for Charlie Parker and his classical training merged quite by chance.

“I had taken up writing symphonic pieces and had written a symphony piece of an album, Charlie Parker with Strings, where the great man’s jazz group played with three violins, a viola and a cello.

“His people in America heard about it and asked me to send the music and then come over and play it.

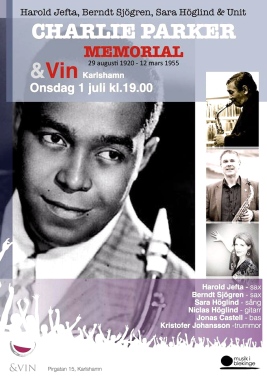

A poster advertising Harold Jefta’s Swedish group playing the music of legendary jazz saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker.

“To my surprise, after they received it, they asked me where the other parts where. I tried to explain that there were only five string instruments on his album. No, they said, the whole symphony orchestra is going to play it.

“So I had to sit down and write additional notes to fit in there – two flutes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four trumpets, three or four horns. I add to add that on to the strings. Strings went to 20. I think I succeeded very well.

“I went over and played it. I was quite thrilled by it all.”

Harold’s love affair with Parker’s music will never end, he says. He plays all Parker’s material.

“The best solo he ever played, and the most difficult, was Embraceable You. He starts improvising right from the start. I heard it when I was 17. I almost fell over. I was still living in Matroosfontein and that, to my mind, is the most difficult solo in jazz history.”

Harold might have a strong preference for the American jazz influence in his playing, but it has not, after such a long time playing it, shut out his love for the music he grew up with.

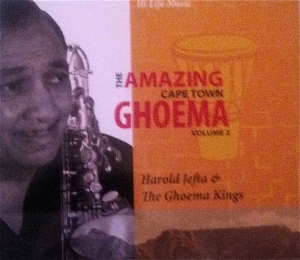

A few years ago, on the instigation of an American, he was contracted to do a “ghoema” album before the “music dies out”.

“I grew up with ghoema. My mother used to run behind me and pull my ears when I walked behind the coons in Goldsmith Rd Salt River. I actually wrote a tune called Goldsmith Rd and everybody likes it.

“I went to Cape Town and I got all the best guys, like Alvin Dyers, Robbie Jansen, to play on it. I wrote about 30 tunes and the music is deeply rooted in the Cape Town street music, carnival street music.

“Of course, I got a lot of criticism for this kind of music, for playing it, since I had been playing jazz all the time and suddenly I make an album that is different, that is steeped in street music.

“You know, the only people who slammed this music were the snobs. Even some of my relatives, they don’t like it. But it is because of the snobbery that ghoema couldn’t develop properly. I just feel that way, I might be wrong, I might be right.

“I won’t say who criticised me for it – you’ll read it in my book later. You see, the people who created this music were the poorer class, the broker boys selling fruit and vegetables on the streets around Cape Town. They used to sing uiwe, more kommie druiwe and stuff like emma ko’ lê ma’ . . .

“Now the people, the snobs, the people who wanted to be white, the play whites, I’m not scared to say it, they stopped that music because it reminded them of the broker boys and the poorer class.

“They want to listen to Bing Crosby that time. The snobbery of the ghoema was a big downfall and still today you find the snobbery going on.

“When I went back to Cape Town after 40 years, I noticed the snobbery was still there. They’d rather listen to Michael Jackson! Man, what the hell! The old people’s music, it’s an art. It’s incredible, that music is going to live forever because of musicians like Dollar Brand, Alvin Dyers, Robbie Jansen.

“I have been so busy with jazz, I’ve been neglecting this. But it is not too late.”

Harold has a high regard for what Dollar Brand did for ghoema.

“Dollar mixed jazz and ghoema. When he went to New York and elsewhere overseas, he told me he could go to clubs and play ghoema all night and people enjoyed it. He does it he’s way, but it’s a very good combination.”

Harold is now pre-occupied with finishing his life story. He has about 300 pages or so “of scribbles” to finish it off.

His biggest dilemma is what to include and what to dump. He says it is necessary to acknowledge people who played with him, like his cousin Kenny, pianists Henry February and Arthur Gillies, Durban drummer Gamby George and Bryan Abrahams, a Cape Town drummer now living in Melbourne.

Home is Karlskrone in Sweden (now he speaks better Swedish than English) but a part of his heart will always be in Cape Town. He has three daughters and a son from first marriage, named after Ornette.

“My daughters play the violin and cello and they all play in the same symphony orchestra. I have played with them and I’ve a lot of funny stories to tell about that, but they will scold me like hell. I get told: ‘hey Dad, you think you know everything’.”

Harold says his health “is perfect, and I’m playing like a devil”. In December last year he played a number of gigs in Melbourne. By the time he got home in January there was a message for him from Maurice Gawronsky to say that there were gigs for him in Cape Town.

So, Cape Town will be blessed by at least four gigs featuring Harold’s Swedish group (see inset).

Make the most of it Cape Town. Harold says candidly he wants to do these things before he gets too old and starts forgetting.

Back in 1950 he was featured in The Post newspaper, playing his clarinet, as a star of the future. He hasn’t had a bad run by anyone’s standards.

Back in the day . . . Harold Jefta with one of the early Golden City Dixies groups with whom he toured before leaving South Africa in 1959.

All photographs sourced with permission from Harold Jefta.

All material is this blog is copyrighted and permission has to be obtained to reproduce any parts of it.

Where is Corinne Harris, what happened to her?

LikeLike

Hi Harold, I dont work with all this social media shit. Send me your number and I will call you. Love D

avid an Stavel

LikeLike

Hi there, wondered if you remembered the Dawson family that lived in Kipling Street, Cape Town. I am married to Norman, the youngest son of Harold, and he is always talking about musicians coming to the house and jamming. We live in France now and would love to make contact.

LikeLike