Ivor Wagner . . . guitarist, keyboardist, bassist, lawyer. He played with the Big Beats, Respect, Tony Schilder during the Sixties and early Seventies.

In the Sixties, South Africa’s pop music scene, and particularly Cape Town’s, was dominated by Durban’s soul sensation, the Flames, and Uitenhage’s Invaders with their more home-grown sound. They drew in the big crowds and sold records like no other. But before them, making their own waves on the music scene, were the Big Beats.

“The Big Who”, you ask. Yeah, the Big Beats, Cape Town’s finest from 1961 to their break-up in 1967.

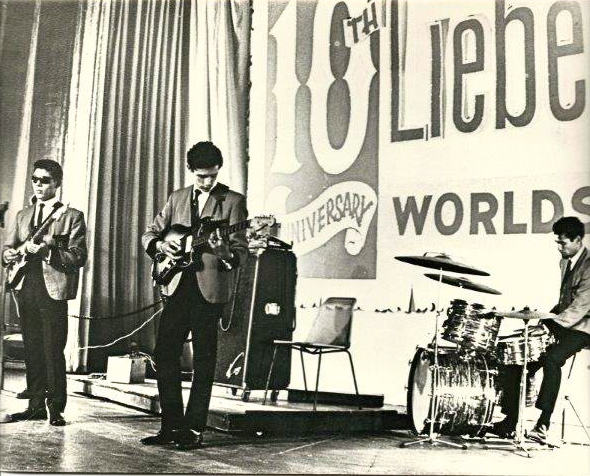

When the Big Beats started pop music was enthralled with Elvis Presley and Britain’s the Shadows fronted by the then cherub-like Cliff Richard. At the height of their popularity, the Big Beats’ line-up comprised “Rosario” on vocals, Ivor Wagner on lead guitar, Ronnie Atkins on rhythm, Joey Cleophas on bass and Charlie Ockers on drums. There was nothing exceptional about the band at first – except for the fact that two of them were blind, Ivor and Joey. Initially that was more of a talking point than their music, but gradually they turned that around and fans got hooked on their renditions of the Shadows’ tunes – the “hot” sound at the time.

Central to that sound was singer Rosario doing cover versions of an up-and-coming Cliff Richards’ hits of the time (The Young Ones, Bachelor Boy, Summer Holiday) but more so, Ivor taking Hank Marvin’s lead role on the Shadows’ instrumentals like Apache, Foot Tapper, The Rise and Fall of Flingel Bunt). The clean-cut, boy-ish Ivor captivated the fans with his dexterity and smooth delivery on guitar.

It surprised no one then that, in time, Ivor Wagner was the face and sound of the Big Beats. They packed out venues across the country. And yet, even as Ivor was the prime mover in getting them to the top, he was also the main character in their eventual demise.

“Yes, that is so very true,” Ivor said when I caught up with him living in quiet retirement in Cape Town. “We, the Big Beats, didn’t want to let go of the Shadows. Or shall I say, I didn’t want to let go. If I let go of the Shadows, my entire image would collapse. I was lead guitarist and by not playing Hank Marvin, which I was known for, famous for, my entire ‘Ivor’ would disappear. I was too afraid for that to happen so I wouldn’t let the group change at all. I insisted that we kept going with the Shadows.

“Of course we became less and less popular. The Beatles took over and all the other Merseyside bands took over and all the new bands went all Liverpool and we got left behind.”

Ivor says it matter-of-factly but there is no disguising the still-lingering disappointment in his voice almost 50 years after the demise of the group. But Ivor Wagner, the Sixties legend was always one to see, as it were, new opportunities. He went on to playing underground music with Respect, jazz with Tony Schilder – and gaining a law degree along the way.

Where it all started for young Ivor

It’s been a long and remarkable journey and the 72-year-old can chart it with precision all along the way. And he hasn’t allowed his blindness to be an impediment under any circumstance.

“I wasn’t exactly born blind. The problem started very early. My mom realised I didn’t look quite right at about 18 months,” Ivor says. “So she took me to a doctor and I was diagnosed with very heavy cataracts. Nowadays it wouldn’t be a problem, they could remove it, but in those days, they couldn’t remove it, it was too thick. I subsequently contracted glaucoma.”

By the age of five Ivor had lost his sight altogether and, of necessity, he attended the only facility available to blind black children in the Cape, the Athlone School for the Blind in Bellville South. It was here that he received his introduction to the guitar.

“Music was never taught at the school but the guitar was a very popular instrument among the boys. The school was 90 per cent African and they played kwela music. It was just a hobby and I played in a few combos at the school.”

Ivor left school at 18 and had no sense of his future and employment other than that dictated by his blindness. That was to change when he met a man called, Peter Marais (yes, the opportunistic politician that has variously amused and enraged Cape Town over the years).

“He loved singing like the Platters and a few Elvis songs. He came around one day and heard me strumming. He said he knew a few guys in Maitland and he took me around to them,” Ivor recalled. “Let me be clear about this, Peter Marais was never a member of the Big Beats although he claimed to be so. He did sing occasionally. He was unreliable. We abandoned him. We ended up with Rosario and he was brilliant.”

That was the birth of the Big Beats. The first line-up was Ivor, Charlie and David Oosthuizen on rhythm.

“We were quite a peculiar group. We didn’t have a bass and I brought in Joey Cleophas. He was also blind and was at school with me. I also brought in Frank Rosario Miller.

“The band was only one year old when David was killed. A bus ran over him. We were just making a name for ourselves when he got killed.”

Initially, Ivor says, the Big Beats replaced David with a guitarist called Goodwill (“Goody”) but he was eventually replaced with Ronnie Atkins.

“Ronald became our resident and very efficient rhythm guitarist. In fact, he would have been a much better guitarist had I given him the opportunity.

“We made a very big name for ourselves nationwide. We copied the Shadows. I was dubbed Cape Town’s Hank Marvin and we did it quite well. Rosario sang all Cliff Richard songs. When the Shadows came to Cape Town, one of the newspapers actually had a centrespread with the Big Beats on one side and the Shadows on the other. The juxtaposition made an incredible impact on the Big Beats from a publicity point of view.

“It was a clever thing to do because we were riding really high then. But let me tell you this, believe me, and no one will, but honestly we never really made money out of it. We never became rich out of it.

“Many thought we were probably making money, but we weren’t and it was a sad affair because I was so hoping the lads could earn much.

“Our format was wrong. We bought the instruments as a group, not individuals. So the group assumed the debt. Instruments were very expensive those days. I mean Fender guitars and Vox amps and Fender bass and Premier drum sets and god knows what kind of PA systems. We had expensive equipment, so the debt was enormous. And we played for £5 [about R10 then] a night. We are talking 1963.

“We played Friday night, Saturday afternoon, Saturday night, Sunday afternoon. Let me give you a typical weekend. Friday night say Athlone Town Hall. Saturday afternoon Elsies Civic, Saturday night Tiervlei Civic, Sunday afternoon the Mermaid club. Sunday evening the Kismet cinema. So over the weekend we would earn about £25-£30 [R50-R60 then].

“We drew huge crowds, but we were so dumb, were so utterly and completely naïve. We hadn’t a clue from our arse to our elbow how to run the Big Beats. It was a complete business shemozzle. I was one of the most naïve idiots during that whole spell.

“It slowly came apart and we split in ‘67. Our bookings came less and less. We couldn’t get work anymore and the guys just felt we better just give it up now. Charlie decided he would take his drums with him. Joey decided he didn’t want to play anymore because he wasn’t earning anything and we were just paying off debt after debt after debt.

“There was no incentive to go on. I really have to accept responsibility for the group’s downfall because in ‘63 or thereabouts, just after the huge The Young Ones, with Cliff Richard, the Beatles came out with things like She Loves You, I Wanna Hold Your Hand, Twist and Shout. The Beatles were huge. I preferred the Shadows and we got left behind.”

It was also around this time that the Flames and the Invaders became prominent and Ivor has his own take on the two bands.

On the Invaders: “Their musicianship wasn’t of a very high quality, but, god, they appealed to “gam” because they played lots of kwelas and lots of sambas and their lead guitarist wasn’t bad at all. He played OK.”

On the Flames: “The Flames, on the other hand, were something different. They were a much more sophisticated and mature band and they played brilliantly. Their recording of For Your Precious and Tell It Like It Is . . . they did those two brilliantly. And they made a very big hit of it. Not only that, they made a recording where brass was added to their backing track. They made a very big impact.

“The Big Beats went to Durban to play in a battle of the bands contest. We came away with our tails between our legs . . . an absolute disaster. I think the Flames won it . . . and we were riding quite high. We spent quite a bit of time playing around in Durban. It was a good experience. And no bloody money for it!!”

Although Ivor was an accomplished guitarist, he never quite made the grade as a vocalist.

“My voice was not there, I just couldn’t sing properly. The other lads, Charlie and Ronnie, they did a little bit of falsetto, second voice for Rosario. I, for my part, did two songs, one called Barbara Ann and Mellow Yellow by Donovan. We did it just to fill the time when we couldn’t think of anything to play.”

After the Big Beats broke up Ivor floated around aimlessly for a while and then hooked up with a white musician, Brian van der Poel.

“Brian had come to the Big Beats and he said he wrote songs. He brought us one, Love is For Fools and we recorded it for him. He was quite happy with it.

“When the Big Beats broke up, we became very good friends. He started a group and they were looking for a keyboardist. That gave me a reason to buy a Hammond organ. I bought one but my keyboard playing was useless, but they had a lead guitar.

“We started rehearsing and playing. It was an appalling group, very poor, struggling. I was used to a very good standard, you see, and when you are struggling with poor musicians, it’s not very easy to handle that. “I’ll never forget this . . . we went to the Arthur Seat Hotel, the four of us, in Sea Point for an audition. They money they offered for 2-3 nights a week was very good. At the end of the audition the manager said, ‘I like you guys, I will definitely talk business’.

“When we saw him again, he asked, ‘Is one of you coloured?’ I felt my face going red hot? We all went ‘who’? He said, ’I’ll be in touch’ — but he was never in touch again.

“Apparently, one of the kitchen staff saw me, and of course the Big Beats were well known. He called the manager and told him ‘but that bloke’s a coloured bloke, you can’t have him playing at the Arthur Seat Hotel’.

“We never got the gig, it would have been good fun.”

Playing with Respect and respect for Tony Schilder

But, it was the late Sixties, Cape Town was alive with clubs like The Stardust, The Soul Workshop and Columbia ’68. Bands were dime a dozen with a shelf life of months not years. The newly formed Rockets were already going through changes. The Raiders had imploded and spawned the new hot group, Respect , the Lunar Five was on its last legs. Blink and you’d miss something while you were blinded by the psychedelic lights that were all the rage then.

Ivor’s break from the music scene was, as expected, short-lived.

“It wasn’t long after that [the Arthur Seat Hotel incident], I was sitting at home with my new Hammond organ when Respect’s guitarist, Issy [Ariefdien] turned up. I knew Issy from his former group, the Magnets, they were a lovely group, and Issy sang very well.

“He wanted to know if I had the keyboard and what I was doing with it? He and the group’s bassist Melly da Silva came to tell me about the kind of music they played and all they needed was a keyboard player.

“I went and played the organ with them and it took a long time to come together. We had good times in that club in Athlone, Columbia 68. Issy and Melly had to carry that heavy organ up and down those awful stairs. Noel Kistima was on drums and Tyrone Macranus and Issy Mohamed made up the rest of the group. Tyrone did Georgia brilliantly. He had that lovely gravelly voice and Noel was a solid drummer.”

Just when it seemed that Respect was going to be the next big thing, it all went pear-shaped with the group. It was as if the Cape Town scene was a mirror image of what was happening in the music Meccas elsewhere with groups like Clapton’s Cream.

“I was very sad to see Respect break up. It was the greatest blow. I was just beginning to find my feet with it, I was beginning to enjoy myself.”

It wasn’t long before Ivor was again headhunted and the new venture was to tax his musical expertise once more.

“By some fluke, pure fluke, I became Tony Schilder’s bass player in December ‘69. He called me and said he was looking for a guy called ‘Vonkies’ who was bass player with the Lunar Five. I had no idea where to get hold of ‘Vonkies’ and when he found out I wasn’t playing myself, he asked if I could play bass.

“Tony told me to come to the Three Cellars club that night because he was desperate for a bassist and I was his last resort. The fact that I didn’t even have a bass guitar did not deter him. He said he had one and he would call out the notes for me.

“When I got there, I found this appalling instrument. I struggled through the evening and at the end he said, ‘look, if you want the job, it’s yours’.

“So I went out and bought myself a bass for £25. I still have it. It was the greatest musical education I could ever have had. It was the greatest privilege to play with Tony. I learnt from that man a 1000 times more. The three years I spent with Tony was a complete universal change for me.”

Initially it was just a jazz trio with a drummer but soon after Rosario was brought in and Ivor says they became a foursome of note on the nightclub circuit. They played Maxims, the Lido, and Three Cellars.

“We made a helluva impact as a quartet, they were all white clubs, we never played the black side. But we never played as white. Tony couldn’t have passed for white anyway.

“They said you could play in private clubs, as there was no restriction there. As long as you didn’t play public licensed places like hotels. That was the rule at the time. But even then the white musicians used to complain because the coloured musicians were taking their jobs.”

Ivor’s music experience had taken him through the diverse genres of pop, soul, psychedelic, underground, heavy music and jazz. What was his first love? “I love jazz now, but I do have a catholic taste. I don’t listen to very heavy jazz.

“There was a time when pop was pop and jazz was jazz and the twain would never meet. But there came a time when people like George Benson turned pop music into a jazz experience of note. It gave the jazz lover the total satisfaction of listening to jazz while enjoying the vibrancy of pop.”

A man in awe of Robbie Jansen

And what about his regard for his fellow musicians in Cape Town? “I loved the Magnets [one of the top groups in the northern suburbs in the mid-Sixties], and I developed a tremendous respect for Robbie Jansen. That man makes me cry when I think about him. I listen to some of his recordings and I get terribly moved by it.

“I’ll tell you why there is a special place in my heart for Robbie Jansen. Robbie credits me with his success, which is totally wrong. I am moved by his claim but really, it is not right. He would tell everybody ‘Ivor Wagner made me famous’. But it is not true. He did it in his own right. The only thing that happened was Robbie participated in a talent contest and I singled him out as the best musician there. And that was it. He became the winner. But he speaks as though I put him on the map. Robbie Jansen put himself on the map. He was just a brilliant musician. I couldn’t match him at all. There was nothing in Ivor that could stand next to Robbie Jansen. He was just a brilliant, complete musician, brilliant saxophonist and lovely singer. He touched me immensely.

“Then of course there was the Schilder family. Now those people one must never forget. Every single member in that family was a brilliant musician. I played with Tony, and I really still think Tony was one of the nicest people – he may not have been the most brilliant, but he was the warmest musician I ever played with. He just knew how to keep his band together.

“Apparently Tony would always say Chris was the most technically brilliant of all the members of the family on piano. But I did listen to Chris and I always felt Tony was the nicer person to play with.

“Then of course there was Richard . . . also a pianist. These guys had their own jazz trios. Then there was Phil, Phil was something else. He was an all-round musician . . . a singer, bass player, guitarist, drummer, Phil was just so complete in every respect. I think the Schilder family in their own right deserve to be acknowledged and remembered by Cape Town.”

He has an optimistic view of where music in Cape Town is heading with the current crop of youngsters coming through and the emergence of a new, classier “goema” music.

“I can’t get a true description of what is happening in Cape Town [with this new genre developing – goema music]. I will say this, Cape Town has talent, there is talent in this town worthy of note. There are guitarists, drummers, keyboardists. I went to listen to a band recently. It is incredible what these guys do. No, I don’t see the emphasis of ‘gam’ music or township music. There might be that of course, but remember, the old saxophonist of days gone by, they used to sound like the old fishmongers. That’s gone. The horn blower on the fish cart, he used to call people to tell them the fish cart was in area to tell them to come and get their fish. The old saxophonists used to sound exactly like that.

“Nowadays they are a totally different breed. There are some brilliant guitarists, you’ve got a guy called Richard Caesar who plays exactly like George Benson and he sings very well.”

The Sixties and the Big Beats and Respect had passed and Ivor had essentially disappeared from view while in the white clubs with Tony Schilder. When next the Cape Flats heard of Ivor Wagner, he was in London, embarking on a whole new life with his young family.

Life in Swinging London — but not for Ivor

“London was a totally different stage of my life,” Ivor says. “I had two totally different sides to my life in South Africa. During the beginning of the Big Beats, ‘62, ‘63, ‘64, I was a in fact a basket-maker, I worked in sheltered employment, what was then called the Civilian Blind Society in Salt River Rd. I worked there until 1966 when I got married. And then I got a job as a switchboard operator with Coloured Affairs and I went to their Bellville Office.

“During that time I met a guy called Glyn Hermanus, he and I became exceptionally good friends. Many people who saw us, I wouldn’t have blamed them if they thought that we were so close that there was some sort of homosexual relationship between us. Nothing like that at all.

“Glyn and I were two virile men in pursuit of wine, women and song continually, but he was a student. He became a medical doctor. Not only was he a student, he was very, very politically aware. He used to talk to me about politics. I was as dumb as they come. I couldn’t talk politics, I didn’t even know politicians’ names, I had no idea of political thought. Glyn on the other hand, two or three years my junior, was brilliant, he engaged in debate, he always talked about all kinds of controversial topics. And he said to me one day: ‘Ivor, how confident are you about keeping music as your means of earning’.

“I enjoyed playing but you had to be a star to make it worthwhile. I didn’t think I had that kind of ability to become a star, a virtuoso.

“He said to me he thought I ought to go to school. By then I had already achieved my Std 6 and I wasn’t going to go any further. I was 28, 29 years old. He suggested I try getting matric via correspondence.

“He enrolled me with the Rapid Results College and I started learning. God, it was difficult. I hadn’t been in school for years. I left school virtually at the age of 15 and I was so thick in the head, nothing made sense to me. The point is, I knew that if I was to get matric, I also had to go to university, and I didn’t think South Africa was the place for me to do that.

“In any case, the politics of the country just drove me bananas and I said to Glyn I wanted to make an effort to get to the UK. I won’t go into the detail about how that came about but at the age of 30 I eventually did go to the UK in 1972, and that is when I figured I had to pursue a totally different avenue of learning . . . my music took a back seat.”

As a young man, Ivor always cherished ambitions of being a physiotherapist. Even though he had his music, he still had a day job as a basketweaver at the Civilian Blind Society, a job he described as “soul-destroying, churning out one basket of another”, and then a switchboard operator. But doing physiotherapy as a blind person was out of the question – the South African National Council for the Blind catered for white blind people only.

“I went to Wolverhampton University where I did a law degree and I qualified as a solicitor there and practised property law for over 20 years. I was 40 years old when I qualified and it took me ages to find a proper job.”

He would not have been able to obtain his degree and practise as a property lawyer without sighted help, he says.

“It was a different kind of life. My guitar playing took a totally different character.” The “different character” Ivor spoke about with regard to his music was the acquisition of an acoustic guitar. He dumped the lead guitar style that he honed during his Shadows-playing days and started teaching himself to play solo pieces.

“I developed a style which many people found very pleasing which I felt happy with. But I have never been able to perfect it. It became an individual style and it can be very listenable but my weakness is my playing is inconsistent, otherwise I would have gone public long ago. I played very well one day and the next would make a complete mess of it.

“I so much want to record the stuff I can play, those solo pieces. I also started composing my own stuff. I did songwriting for female singers, that was what I had in mind. I never really found a singer but I had female singers in mind. I wrote quite a few songs, I slowly started acquiring equipment to record these things. I got myself a synthesizer, a sequencer, quite a few bits of pro audio music equipment. And then I began to record my songs, I arranged them, performed them and recorded them as instrumentals, meaning that when I find a singer I would say to them, ‘listen to this song’ and I wrote the words for them.

“I’m still sitting with that stuff, it is collecting dust. It is one of Ivor’s most famous failing efforts.”

Ivor says it was always the intention to come back to South Africa with wife Lavona and their children, Wayne and Janine. They visited Cape Town every year to see family, bought a house in 2003, and in 2006 moved back “lock, stock and barrel”. The move back to Cape Town brought its joy but that happiness changed to an intense low for the ebullient musician – his wife of 40-odd years died after a major stroke.

“It was so very sad, Lavona was so looking forward to her retirement, she only had three-and-half years of it and then she died. It was one of the greatest blows. I have never known such pain as I did then. When Lavona and I used to talk about the time of our passing, it was always on the assumption that I would I go first.

“So when Lavona did go first, I was caught out so completely that I literally fell on my face. I didn’t know how to handle it. My home just came apart. I had to find someone to put my home together again very quickly. And I found a carer who was brilliant, she did a very good job in just keeping my home going.

“I enjoy life now, I’ve gotten used to the idea of being alone and I am the world’s greatest flirt now. I really go from woman to woman. I think I’m enjoying the twilight part of my life.”

Ivor was thrilled at the recent reunion gig of Pacific Express but does he entertain thoughts of jamming with guys of yesteryear?

“I have thought about it but I would be a complete disaster on that stage. For one thing, my guitar playing to match that kind of thing would be so appallingly poor. Also, I have developed a solo guitar playing style, which is difficult to break away from now. Put an electric guitar in my hand now and tell me to go and play with a group, I would be utterly floating around, I wouldn’t know where to turn. Put an acoustic guitar, like a classical guitar in my hand, then I can do things for you.

“There had been talk of myself, Charlie and Rosario getting together for one big bash but it never came to fruition and I wasn’t living in Cape Town, so to organise it was near an impossibility. Charlie died, Joey died, and Ronnie. The only one still with us is Rosario and he is Canada.”

[This material is copyrighted. Permission has to be obtained from the author to reproduce any part of it.]

Love these stories. I attended a number of the “Big Beat’s” shows.I also remember Elsperth Davids singing with them, in the latter years. Great band.

LikeLike

Good stuff Warren, this is the sort of music history I was talking about. Get the impression he is not bitter like some of the old guys get.

Talk to Zayn about the pre-Express days.

Must say I felt some pride from Ivor’s remarks about Robbie’s recordings.

LikeLike

Excellent piece of work. The candidness and self effacing introspection was a pleasure to read. What memories of the evolution of the music scene in South Africa over the years. I say we get Ivor and a host of the people he has mentioned in a get together which doesn’t have to be on stage. The sheer value of the collegiality and appreciation of each other would be priceless. Let’s not forget, we have so much to be grateful for.

LikeLike

Hi Warren,

Before the ‘Pacific Express’, was the ‘Pacifics’. Whatever happened to those blokes. Alby Ontong, David Ellis ,Viv Raisenberg and Trevor Lambert (deceased). Also see if you can get some info on the ‘Missiles’. Best 60’s band.

Thanks for all the information. Just great.

LikeLike

Philly, I will try to catch up with the Missiles’ Charlie Anyster when I get to Cape Town. He was top class, streets ahead of the others with his music. I reckon he would qualify as an “elder” by now!!!

LikeLike

I lectured with Charlie at the then Bellville College of Education. Me Technology as a subject and Charlie in the Music Department specialising in classic violin (could you believe). Being a great fan of The Shadows I found Ivor Wagner as exceptional on that Strat and followed the Big Beats all over Cape Town. Nice to read Ivor’s recollections.

LikeLike

Warren, Eddie or Colin Stoffberg should be good sources of info on the Missiles and Clash.

LikeLike

What an interesting read

I often chat to Ivor (he is my dad’s uncle)

But I doubt I would get this detailed picture of his life.. He has told me so many stories, and yet I’ve never know the history of his musical career. So thanks for the article.

LikeLike

Hi Devon

I hope this email finds you well.

I am hoping you can help me. I am a friend of Ivor’s. I moved to Pretoria in last year and Ivor and we lost each other some how. I had contact with Ivor in January and February, because I helped him with his Iphone. Unfortunately my laptop broke and I lost his email address. I sent him smses and tried to call, but his cell number I have is off and his home number only rings.

I am worried about him and I am hoping you can shed some light on how he is.

I know that he is usually visiting his children in London this time of the year, so if possible, can you send me his email address please.

Thank you in advance.

Regards

Christine Barnard

LikeLike

Hi, great reading your story Ivor. I learnt a lot from you in the Sixties. I am still playing and still do lots of the Shadows stuff. We spent some great years together with your brothers, Neville, Paddy, Manfred, and Mervin, — not forgetting your dad Giltie. I used to sip his wine [torino] and your sisters Mercia and Lavonia. Sad to have heard of your wife passing on.

I still use the tremelo arm to great effect. You taught me the true meaning of its use.

I use a Fender American Strat and try to play as often as possible. It would be nice to visit and see you again. You friend

Cyril Francis — The Jets

LikeLike

I still remember you. This is so interesting, I really enjoyed. I need your permission to share on facebook giving you credit of course. I am still in Cape Town. Hope you saw my comment re Charles Anyster (Missiles)!

LikeLike

John,

I noted your comment about Charles Anyster. I have not had contact with Charles for decades. I wouldn’t mind getting a telephone number from you or anybody out there. I’d like to feature him on these pages.

Warren

LikeLike

I’ll try my best to get Charles’ contact details & then forward to you…….

LikeLike

You’ll find Charles on Facebook.

LikeLike

I have goosebumps!!!! Tears in my eyes. Thank you for the read. I am Tania (Atkins) Strydom, eldest daughter of Ronnie Atkins. My youngest sister sent me this link, while I was having a horrible day at work today. This was a breathe of fresh air. Big Beats – Legends!!!! We heard aaaalll the stories 🙂 My sisters and I grew up with this music, uncle Ivor and my dad playing the Platters, Shadows and later some classical music. I’m going to make a point of going through his cassettes where they later recorded there guitar playing at weekend braais – need to get it onto another form of media. I wish I could post this to my pops in heaven.

LikeLike

I received this link from my sisters and was so excited when I saw “The Big Beats” mentioned. Growing up, myself and my 2 sisters heard countless stories of the Big Beats and was even privileged to see my Dad and Ivor play on the odd occasion when he would visit. You see, we are the daughters of the late, Ronnald Atkins and he was a brilliant guitarist as mentioned in your article. We still reminisce with those photos of them when they were in their prime as my Dad would say. Thanks for making my day:-)

LikeLike

Phenomenal and deeply moving story. My masters thesis will be based on Zayn’s life. I had the privilege of briefly working with him before the PP Arnold Caie Town tour. (I contacted PP Arnold two years before about the possibility of coming to Cape Town. I had no idea what I was doing but I managed to do it with Clivr Newman and Glenn Robertson’s help).

My passion is legacy creation, preserving and telling the narratives of our people particularly our forgotten music heroes. Indeed one of my projects is to create a legacy work, a coffee table hard cover book honoring as many local music legends as possible. Many of you will know my brother Dmitri Jegels.

Warren I would love to meet you and thank you for putting up this site. And ask for your assitlstance in both sourcing information for my Masters thesis and the legacy project.

LikeLike

Sure, now let’s just work out the logistics. Your place or mine?

LikeLike

Thanks for replying so soon. Rondebosch later in this week can work. Send me your number and we can whatsapp.

LikeLike

What an interesting read!!!

It’s Charles OKKERS (aka “Charlie” Okkers) and not OCKERS…as incorrectly stated in your blog.

Yes, I fondly remember my dad (Charles Okkers R.I.P) telling my siblings (Markham, Sonya, Cyril and Charlene) about the “good Olde Days as drummer for The Big Beats”.

LikeLike

Renee,

Thanks for setting the record straight. I will amend the article accordingly. You wouldn’t have any photos of your Dad play8ing with the Big Beats would you? I’d like to include it on the blog.

Warren

LikeLike

Hi Warren

Thanks for acknowledging…& Yes you’re most welcome to check-out their heyday photo…Just check your Inbox 📩.

Regards

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this fantastic article. Ivor worked as a property lawyer with me for many years – handling work for the British Coal pension fund which invested heavily in commercial property. Although Ivor mentioned his time with the Big Beats, he told me very little about his earlier career as a musician. So this has given me the other side of his life which is so impressive. Sadly, I am writing this only a couple of days after Ivor’s funeral. May God grant him eternal rest.

LikeLike

Hi, Warren, I also had connections with the Big Beats through the band I was with, Goodwill and myself formed a group, I had an opportunity to play with the “beats” when Charlie was in semi retirement due to his kidney problems, but I was a very poor drummer to Charlie’s standards, I had the priviledge to attend his funeral. Thanks for your article.

LikeLike